-

Posts

4,765 -

Joined

-

Days Won

6

Everything posted by SteveMc

-

The John Williams Concert Work Listening and Discussion Thread

SteveMc replied to SteveMc's topic in JOHN WILLIAMS

The Olympic Spirit (1988) Williams returns to the theme of the Olympics. This time around, it was NBC who commissioned the piece, as theme music for their Seoul Olympics coverage. Thus, the work is not strictly a concert work, but, like The Mission, television broadcast music structured in concert work fashion. I suppose, however, the connection to the rest of Williams's Olympics overtures, helps make a case for its higher status as a concert piece. Unlike the Olympic Fanfare and Theme, this piece is more straightforward, a bit less daring and programmatic and more filmic in its treatment of theme and variations. It does have the essential ingredients of memorable brass motif and stirring long lined melody. It is joyous and inspiring, if not quite iconic in intent or execution. I've always liked it a great deal regardless. Here is the 1996 recording with The Boston Pops. -

What Is The Last Score You Listened To? (older scores)

SteveMc replied to Ollie's topic in General Discussion

The Russia House is my favorite Goldsmith. -

La-La Land Records has another Williams release planned for 2021

SteveMc replied to Jay's topic in JOHN WILLIAMS

Concerto for Kazoo when? -

I love Tauriel's Theme

-

Hard to ever beat Powell these days.

-

This is fantastic. Has he done any concert work?

-

TLJ and The Post were the best. I greatly respect Phantom Thread, though.

-

John Williams & Berliner Philharmoniker 14th/15th/16th Oct 2021

SteveMc replied to MaxTheHouseelf's topic in JOHN WILLIAMS

The Berlin JW performance vs. Vienna JW performance poll thread will be epic. -

La-La Land Records has another Williams release planned for 2021

SteveMc replied to Jay's topic in JOHN WILLIAMS

I want to believe.... -

The John Williams Concert Work Listening and Discussion Thread

SteveMc replied to SteveMc's topic in JOHN WILLIAMS

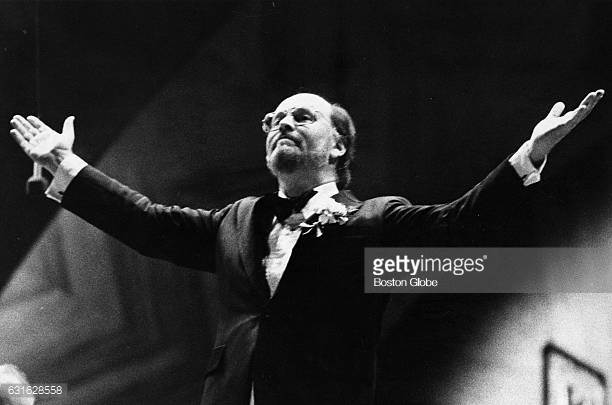

We're Looking Good (1987) Rollicking and upbeat occasional overture with a good deal of 1941 in it written for the Special Olympics. There's a version with lyrics too that appears lost to time. Here's John conducting it. -

The John Williams Concert Work Listening and Discussion Thread

SteveMc replied to SteveMc's topic in JOHN WILLIAMS

Celebration Fanfare (1986) Two compositions today. First, a celebratory piece commissioned by the Houston Symphony to mark the sesquicentennial of my adopted home state of Texas. As noted in the link below, it was part of a larger project of commissions from a slate of major composers to mark the event, and was performed first by the Houston Symphony and then by Williams with the Boston Pops, during which time it was recorded for broadcast. https://www.johnwilliams.org/compositions/concert/celebration-fanfare AFAIK, that broadcast has not surfaced. Neither has any audio I know of from a more recent performance here in Houston in 2009, detailed here: I wonder why JW did not dust off the piece when he came to town in 2013 with Yo Yo Ma for a concert with the Houston Symphony at Jones Hall. Anyway, on to the next piece: A Hymn to New England(1987) A piece of solemn patriotism that, while written as a piece to accompany a media presentation, is usually ranked as a concert piece. Apparently, the orchestration, and possibly more, was done by Boston Pops percussionist Pat Hollenbeck. As quoted in the link below, he claims to have "basically put it together" from original themes by Williams. https://www.johnwilliams.org/compositions/concert/hymn-to-new-england Here is the piece as conducted by Williams. -

John Williams & Berliner Philharmoniker 14th/15th/16th Oct 2021

SteveMc replied to MaxTheHouseelf's topic in JOHN WILLIAMS

I think it is the perfect non-occasional concert work to drop into a mostly film score concert. -

Part of it might be that, when I first got into JW in 2014, it was his newest score. So, my appreciation might be tinged with that subjective background. But, objectively, I think that is is a wonderful chamber score, each cue having this quiet emotion and sadness. They feel like little musical jewels. For a composer known for bombast and broad strokes, it vividly shows how subtle his voice really is. It also is a fantastic example of JWs leitmotif approach. The harmonic language also impresses me. I listened to a lot of classical in my teens, so a lot of my takes on film scoring is rooted in that, and The Book Thief really fits into those sensibilities.

-

The John Williams Concert Work Listening and Discussion Thread

SteveMc replied to SteveMc's topic in JOHN WILLIAMS

Liberty Fanfare (1986) Composed for the grand centennial celebration of the Statue of Liberty and its concurrent restoration, the Liberty Fanfare is a concert overture somewhat in the Olympic Fanfare mold. Stirring, patriotic, hummable, a grand distillation of 80s optimism. It serves its purpose well and has become something of a modern Americana classic. I enjoy it well enough. Here is Williams conducting the piece during the event for which it was commissioned. And here are two Boston Pops recordings, one with JW on the podium, the other with Keith Lockhart. -

I do think the scores I listed are masterful. War Horse too for that matter. I don't think a masterpiece has to be shocking or out of the ordinary or breaking new ground. Beethoven's late quartets are masterpieces for that reason. Bach's Mass in B Minor is not. But it is still a masterpiece, a culmination, Bach showing off his powers in a titanic way, powers he showed off plenty of times before. I do understand, however, the urge to use the word masterpiece to denote something truly spectacular. The passage of time and the collected opinion of others is often needed to discern this. Even then, there is dispute. Some folks even find Beethoven's 9th not worthy of masterpiece status. I think CE3K, ET, Schindler's List and probably Star Wars are pretty universal JW masterpieces. After that, it is subjective. I'd add TESB (which I find superior to SW), Empire of the Sun, A.I., Lincoln and maybe Jane Eyre right off the bat. Also, I'd still maintain The Book Thief is a masterpiece, but I understand that's not quite a universal opinion.

-

It's an excellent, muscular score. For what it's worth, I revisit it more often than many of his better-known scores.

-

What the blogs say vs. what actual Classical Musicians actually say.

SteveMc replied to jojoju2000's topic in JOHN WILLIAMS

Film music by itself is not necessarily classical music, just as a song is not necessarily a lieder. It depends on composer and intent. Who is the composer? Did he or she have formal or informal training in the classical tradition? If yes, in writing the score, did he or she have a kind of artistic intent that transcends the film? Sometimes the distinction is obvious. Folks like Vangelis and Zimmer have artistic intentions in their scores, but their work is rooted more in popular music than classical. Korngold and Rozsa and Herrmann were classical composers, and all their scores are clear compositions. Sometimes the distinction can be a bit more subjective. Steiner had classical training, but his scoring style was bit more in the direction of light music. But, then, someone could dismiss Vivaldi as light music and I'd find that very wrong. What of John Williams? You can draw a clear line connecting late 19th century classical masters to him. Mahler and Strauss to Korngold to Williams. Rimsky-Korsakov to Glazunov to Tiomkin to Williams. Add to that a healthy does of native influence from American Jazz. He studied piano with Rosina Lhévinne, who encouraged him to be a composer and then studied with Castelnuovo-Tedesco. This is what gives Williams's technique such a compelling quality and the ability to be almost endlessly studied or analyzed. But, unlike a good deal of 20th century classical music, Williams's music is overt. Which is to say it's main point is often obvious and accessible. This is a consequence of much of his music being written for films, which is to say, for patrons and an audience that often demands this. This leads to critiques that Williams's music is thus shallow and subservient, that it represents not the true vision of the artist, but simply reflects the vision of others. Never mind that obvious and accessible characterized much of the pre-20th century artform, this is declared to be backwards emphasis that further proves the essential point, which is that John Williams is not a classical composer, and nor is any of his music truly classical, concert or otherwise. But this is an unfair academic stance that ignores the essential nature of the art form. For much of its existence, classical music was written for others. Wealthy patrons, royalty, aristocrats, superstar performers, a demanding opera industry. And yet, a great deal of this music is still considered artistic works of integrity and merit, the composers lauded as masters, even if they were partly doing the bidding of others. Why? Because the music is judged on its own merit, these factors included in the estimation, but the artistic intention snuck in by the composer also taken into account. Why can't John Williams be accorded the same consideration? Those who do judge him by this older standard rather than the narrower academic art cannot be for all crowd often deem him worthy. There can be honest negative opinions about his work, how it might be too on the nose most of the time, maybe too bombastic, predictable, or how he may not have the greatest structural mastery. But before you can have an honest opinion about John Williams's music, you need to acknowledge that it is classical, since it is rooted in that tradition, even if it is a branch of that tradition a certain school has declared anathema. That might be changing, as I will address soon. First, take the example of Bach. Bach is generally accepted to be one of the all time greats. For much of his lifetime, he was considered a throwback, out of date. For much of his lifetime, he was a hireling. His greatest works were written for others, often on their instructions and with their interference. That he was able to thrive in this environment and throw in the mastery and musical complexity that he did is amazing, and the greatest testament to his genius. Towards the end of his life, he began to have a little more recognition, but still more as a politely respected curiosity than anything. After his death, the establishment overlooked him. Only the geniuses paid him full attention. Finally, when he was dead long enough for him to no longer be passé, he was rediscovered and adored. Williams is not a 1-1 comparison here, he's not in Bach's tier. But, we see similar patterns repeating themselves. Which brings me to my next and final point. Where exactly does John Williams fit into the classical tradition? For some, the medium for which he most often writes and the style he uses marks him a member of a breakaway blasphemous sect that is not fit to be called classical, never mind that it has more in common in those respects to what was classical for 200 years than the modernist take. But this is in fact the outdated view, rooted in a roughly 1920s-1960s modernist stance. Since then, classical music went through a bit of a revolution. Postmodernism. For a point of reference, take postmodernism in architecture. Roughly, you could divide it into three threads. Overall a rejection of the formality and perceived coldness of various forms of modernism, Postmodern Architecture offered an alternative. One thread went for an expressionistic flair, new shapes, unusual forms, shock value even. This thread felt like a logical extension of modernism in a way. The equivalent in music would be Ligeti and composers like him. The second thread I like to call Pop-Postmodernism. Color, vibrancy, familiar or vernacular forms with a twist. Musical equivalents: Glass, Adams, perhaps Morricone. Finally, a certain neo-traditionalism. Architects using traditional principles and ornamentation on newer forms, ranging from skyscrapers done in a pseudo- Flemish church style to buildings almost exactly 18th century on the outside, but completely modern internally. Several post-modern composers have done similar things. Rouse comes to mind. So does Williams. I see his approach as most definitely rooted in postmodernism, his voice one of the most important ones of the movement. You may not like what is has to say, but would anyone try to call a traditionalist work by a noted architect not architecture? Perhaps there are some folks who would, but it is rather absurd on its face. There, this should be pretty much the final word on the matter. I would post it on TalkClassical, but I've forgotten my password and can't really be bothered. -

Citius, Altius, Fortius!: The John Williams Olympic Music Thread

SteveMc replied to Will's topic in JOHN WILLIAMS

So much choice JW, so little time! -

What the blogs say vs. what actual Classical Musicians actually say.

SteveMc replied to jojoju2000's topic in JOHN WILLIAMS

ET perhaps is in the running for that, but I'm rather skeptical about Star Wars being his best. CE3K is my choice for his "best" score. -

What the blogs say vs. what actual Classical Musicians actually say.

SteveMc replied to jojoju2000's topic in JOHN WILLIAMS

The TalkClassical crowd speaks like Star Wars and ET are all JW ever wrote and judge him simply on those scores. They come off as just refusing to take him seriously because he is popular. -

La-La Land Records has another Williams release planned for 2021

SteveMc replied to Jay's topic in JOHN WILLIAMS

It's more poetic that way