Search the Community

Showing results for tags 'John WIlliams'.

-

FYC PROMO on ebay. Tracklist: 1. QUICKSTEP AND THE AMERICAN PROCESS 2. SLEEPING TAD 3. WITH MALICE TOWARD NONE 4. GETTING OUT THE VOTE 5. THE SOUTHERN DELEGATION ARRIVES 6. REMEMBERING WILLIE 7. MESSAGE FROM GRANT AND DECISIONS 8. NO SIXTEEN YEARS OLD LEFT 9. THE TELEGRAPH OFFICE 10. THE PURPOUSE OF AMENDMENT 11. EQUALITY UNDER THE LAW 12. WELCOME TO THIS HOUSE 13. THE AMERICAN PROCESS 14. LINCOLN RESPONDS TO SOUTHERN VP 15. CITY POINT 16. LINCOLN AND GRANT/LEE'S DEPARTURE 17. TRUMPET HYMN 18. NOW HE BELONG THE AGES 19. END CREDITS I haven't seen the film yet. but I think this could contain unreleased music

- 23 replies

-

- John Williams

- Sony

-

(and 1 more)

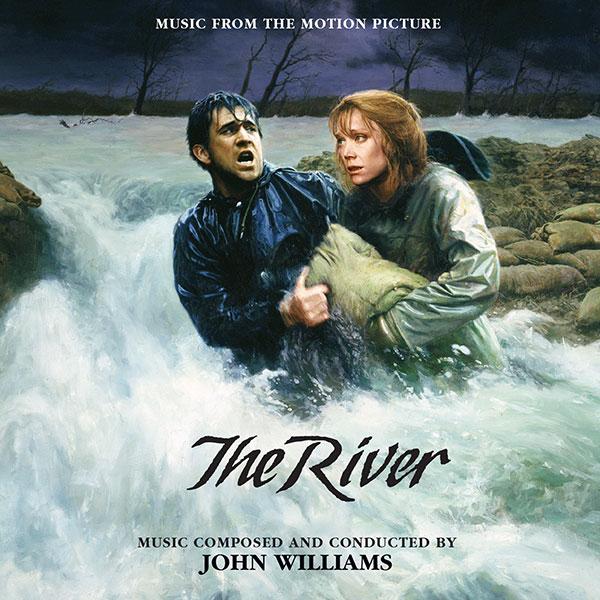

Tagged with:

-

I'll repost my review here at this point and I will be making updates once I have seen the film to make more accurate comments on how the music relates to the story and the drama. Lincoln Original Motion Picture Soundtrack by John Williams http://www.jw-collection.de/images/lincoln_02.jpg A Review By Mikko Ojala The 26th collaboration between Steven Spielberg and John Williams takes them to the turbulent Civil War era of American history, the life and times of Abraham Lincoln. The upcoming motion picture Lincoln focuses on the last four months of the president’s life and the momentous decisions he was faced with during the ending of the civil strife and drafting the 13th Amendment to abolish slavery. Tony Kushner the famed screenwriter and playwright, who previously collaborated with Spielberg on Munich, provided a script based on the mammoth of a historical biography A Team of Rivals by historian Doris Kearns Goodwin, which apparently took 6 years to forge into a workable script as the entire presidency and life of Abraham Lincoln proved too much for a single film to depict. The film boasts an impressive cast of Daniel Day-Lewis as Abraham Lincoln, Sally Field as Mary Todd Lincoln, Joseph Gordon-Levitt as Robert Todd Lincoln, Tommy Lee Jones as Thaddeus Stevens, David Strathairn as the Secretary of State William Seward just to name a few and part of the film crew are the usual suspects in a Spielberg production, the cinematographer Janusz Kaminski, editor Michael Kahn and of course composer John Williams. John Williams is certainly no stranger when it comes to portrayals of American history and Americana as he has scored numerous films in the spectrum of the idiom throughout his career from the rural, frolicking The Reivers and The River to the heart aching string led lyricism of Born on the Fourth of July, and from the Southern flavoured blue grassy Rosewood to the stately nobility of Amistad or quiet heroism of Saving Private Ryan or the brassy valour of The Patriot. His approach to this type of film could be said to be archetypical for such a subject matter, the composer describing his score in a May 2012 interview with Jon Burlingame as written in the 19th century musical language and containing hymnal modalities in the spirit of the American music of the times. So it might not come as a huge surprise to Williams’ dedicated fans that he chose a mix of Coplandesque and his own inimitable brand of Americana to address Lincoln and still this might actually be one of his most outwardly traditional scores in the idiom to date, so strongly he embraces the modes and musical gestures, feel and inflections of tradition of American music. You could say that this new score forms a walk down the memory lane to the long time afficionados of his music as the different facets of his Americana writing pop up constantly on the soundtrack album and we do encounter in Lincoln brass and string writing in line with the style of Saving Private Ryan and Amistad, folk music stylings from scores like The Reivers, solemn sections similar to those in both The Patriot and War Horse and elegiac tones of Born on the Fourth of July, JFK and Nixon, but it has to be said that Williams does not self quote his old music but rather the overall sounds and styles of what has come before and building again something new on this foundation. In this respect Lincoln might not be groundbreaking in style and sound but it is despite of this highly entertaining and accomplished, at times ravishingly beautiful and powerful music which showcases once more Williams’ strengths, his gift for strong themes, deftness of orchestration and dramatic instinct. To enhance the connection of the music to the president himself the composer at Spielberg’s suggestion engaged the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and Chorus to perform the music in honor of Lincoln’s old home state of Illinois and to evoke some of the local musical flavour through their talent on the soundtrack. The Chicago Symphony Orchestra has to be complemented for its vibrant and warm sound and the beautiful and numerous heartfelt solos gracing the album, the playing further elevating the emotional appeal of the music. Violin, trumpet, clarinet, bassoon, horn, cello and piano all receive lengthy solo passages but the entire ensemble creates a very empathetic, resounding and warm sound that feels very appropriate for this kind of music, capturing both the tenderness and the stateliness with equal skill and certainly gives the studio orchestras run for their money. The music on the soundtrack album travels between the two poles of stately reverent and lyrically intimate by the way of some rustic humour, reflecting perhaps the balance of these elements in the film, the public and private persona of the president and the affairs of his office. The above mentioned soloists play an important role in the music and on nearly every track one or more of the Chicago Symphony’s musicians are offered a moment to shine. This serves both the restraint for which this score audibly strives but also imparts a sense of simplicity, honesty and fragility, a certain sense of isolation, giving an impression a man amidst events that are greater than he is, and provides a great deal of emotional resonance to the music. A healthy amount of restraint seems to be a guiding thought in this project to both Spielberg and Williams so as not to overpower the performances of the actors or the reality of the film and the composer is obviously trying to do more with less in many instances, reserving grander musical histrionics only for a handful of moments on the album. This restraint and certain stream lined sparseness and reliance on gentle simplicity does not however dilute the musical expression of the score and I actually feel that it strengthens and focuses it, Williams saying perhaps more emotionally with reduced forces than with a complete symphonic ensemble blowing full steam ahead with brass section blazing through every track. Themes: The score boasts with a whole host of themes ranging from noble pathos to familial tenderness. As it might be clear from the above general description of the music all these ideas share a strong Americana feel, whether it is a down-to-earth and folksy or more classical hymnal one and here as in both of Williams’ recent scores (The Adventures of Tintin The Secret of the Unicorn and War Horse) these themes seem to form a family, that shares common musical roots. The composer’s decision to provide so many different ideas perhaps reflects the different aspects of Lincoln and the people close to him, the themes forming a tight knit fabric of motifs that flows from one to the next with fluid ease on the soundtrack album. Partly as a consequence from this way of writing and thinking Williams doesn’t obviously assign any of his themes a clear central position as the “main theme” of the score that then would be stated and restated with regularity, which might puzzle and frustrate some of his fans, and there are indeed several long and well developed ideas on the album vying for that title, appearing continously from one track to the next. Still after numerous consecutive listens With Malice Toward None seems to be for me the most important and emotional and certainly most memorable of all the themes on the album. With Malice Toward None (Lincoln’s Theme): The name of the theme refers to the second inaugural speech of Lincoln and it is a folk song styled, simple, lyrical and honest melody that could be said to be main theme of the score. It seems to embody the down-to-earth nobility of the main character and his humanity. Coloured with lilting gait of folk music in some settings and slow solemn progression of traditional hymns in others, this theme paints a very humble, thoughtful and gentle picture of the president of United States. Appears on the album: 04 The American Process: 1:18-1:47 and 3:10-end 06 With Malice Toward None 12 Freedom's Call: 0:24-2:29 16 The Peterson House and Finale: 1:49-3:13 and 7:40-8:25 17 With Malice Toward None (Piano Solo) The American Process: A gentle lilting Americana "home and hearth" melody with almost folk song quality, the theme pensive yet optimistic with a sense of earthy wisdom. It is set often in the woodwinds, clarinet, bassoon and flute but this idea is also frequently developed on stately strings or brass, revealing a nobler aspect and aspirations in this guise. Appears on the album: 01 The People's House: 2:16-3:09 04 The American Process: 0:00-1:19 and 2:10-3:00 11 Equality Under the Law: 0:00-1:36 12 Freedom's Call: 2:29-3:18 16 The Peterson House and Finale: 4:50-5:43 and 8:26-9:14 The People’s House: The most dramatic and triumphant of the themes, this noble and heroic idea is built on a leaping four note clarinet figure heard initially on the opening track and soon blooms to a full brass and strings setting, imparting a sense of victory and achievement, probably reflecting political and personal accomplishment. The idea is used sparsely on the soundtrack album appearing only on the opening track and the Finale track, and it seems that Williams is reserving this level of musical heroism for specific and crucial instances in the narrative. Appears on the album: 01 The People's House: 0:00-2:15 and 3:10-end 16 The Peterson House and Finale: 3:14-4:49 Freedom’s Call (The 13th Amendment): A short and direct melody, composed of a series of a few alternating chords, depicts perhaps Lincoln’s just and good aspirations and goals, the 13 Amendment and the abolition of slavery and his gentle wisdom and noble humanity. There is stately grace in this simple yet affecting idea, bridging the public and personal side of Lincoln and Williams offers numerous alternating variations of it throughout the score in different settings from solo piano to brass chorale. Appears on the album: 02 The Purpose of the Amendment: 0:55- 1:39 and 2:26-end 09 Father and Son: 0:34-0:52 and 1:08-end 11 Equality Under the Law: 1:37-end 12 Freedom's Call: 3:18-5:29 15 Appomattox, April 9, 1865: 0:24-1:08 16 The Peterson House and Finale: 0:24-1:20 and 6:19-7:39 The Elegy: A mournful and anguished string elegy, quite religioso in nature, that seems to exude regret, sorrow and horror all in one harrowing theme, a reminder of the Civil War and its ravages. Appears on the album: 08 The Southern Delegation and the Dream: 3:06-end 13 Elegy The Loss and Remembrance Theme: A theme that seems to relate both to Lincoln's personal loss, of his son William, but also to mourning of the tragedy of Civil War and remembrance. It is an unadorned piano melody that expresses bittersweet sorrow with a hint of regret. This musical idea is used sparsely and always retains the same guise, invoked on the piano, the most familial and "domestic" but also emotionally direct of instruments. Appears on the album: 05 The Blue and Grey: 0:00-1:01 14 Remembering Willie: 0:29-end 16 The Peterson House and Finale: 9:29-end *** Track-by-track analysis As I have not seen the film nor do not know the full narrative of the movie, the below analysis and names of the themes are pure speculation on my part, made only to give the piece a structure and to help identifying recurring musical ideas on the album. 01. The People’s House (03:41): A pensive 4-note phrase (a warm nod to Aaron Copland's Appalachian Spring) on solo clarinet, played by Stephen Williamson, opens the album with an air of gentleness and optimism, the lilt of the melody almost asking a question as it repeats several times all the while developing the phrase, strings rising to support it. Flute and clarinet restate the original 4-note idea before Williams lifts the melody forth in key and strings sing out a fully formed upward climbing People’s House theme, noble and stately, as if denoting a moment of accomplishment and victory, brass accompanying the melody warmly underneath. Woodwinds present the second phrase of the thematic idea, slightly more thoughtfully winding melody implicating resolve before it is swept again into a majestically fanfarish and rousing full orchestra statement of this Americana theme, the 4-note motto of the theme slowly receding through the ranks of the orchestra to solo trumpet after the crescendo. Clarinet and flute duet plays a new theme, The American Process, another Americana melody where the two swaying woodwinds interlace their voices in the song-like melody that is dignified and initially almost folksy but soon reaches stately proportions as suddenly glowing violins underpinned by lower brass take up the theme, giving the music an air of importance, solo trumpet rouding out the track with a calm and proud statement of the People’s House theme. One of the stand-out pieces of the album, this is a wonderful way to open the CD but oddly the opening heroic musical idea does not return to the score until the finale. In overall feel this cue sounds like Amistad meeting Saving Private Ryan with a dash of the unabashed heroism of The Patriot thrown in. 2. The Purpose of the Amendment (03:06): A new ruminating and stoic melody is heard on clarinet and bassoon, developing slowly phrase by phrase but then moving to a hopeful and warm string idea, the first appearance of the Freedom’s Call theme, that calmly rises forth on higher strings, the celli and basses playing accompanying figures underneath giving the music a sense of forward progress, the theme perhaps illustrating Lincoln’s ideals and political aspirations concerning the 13th Amendment and healing the war torn nation. Clarinet and horns and trumpets all pass phrases, solo trumpet’s clear tones rising alone for a moment before autumnal strings and clarinet transition again to Freedom’s Call theme in the string section, this time more assured, glowing and reverent, clearly indicating a moment decision. The writing here reminds me of War Horse and Saving Private Ryan, especially Williams’ way of combining flute, clarinet and bassoon voices and the way the broad long lined theme is developed on strings. 3. Getting Out the Vote (02:48): Solo violin quickly and subtly hints at the chords of Freedom’s Call Theme, maybe a nod to the political action taking place during this light hearted cue, before Williams spins a wonderful jaunty Appalachian scherzando or dance for strings, solo fiddle, viola, woodwinds, tuba and light percussion, the music exuding wonderful hoe-down folk music feel and humour. The soloists have their moment to shine, violin and bassoon performing particularly delicious solos. This piece is a delightful interlude that offers not only variety and levity but allows the composer to explore a different side of Americana writing, the style and feel of the piece harkening back to his similar music in The Reivers. A terrifically sprightly and fun piece! 4. The American Process (03:56): Clarinet and bassoon duet once more, this time giving a long rendition of the American Process theme, solo flute joining them and for a while the trio develops the music alone the melody full of tender warmth. Oboe’s lyrical voice has almost a bucolic air here supported by the gentle lower strings before stately and burnished low and slow brass choir introduces a brief first statement of With Malice Toward None that ends in very dignified sounding brass phrases, hinting possibly at official state business. Randy Kerber, the only soloist not from the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, performs a simple yet emotional piano variation on the American Process theme with solo flute ghosting subtly, calm swaying string chords melting into Christopher Martin’s sublimely serene trumpet reading of With Malice Toward None, a perfect depiction of nostalgia and longing, which closes the track in soothing tones. 5. The Blue and Grey (02:59): A dark hued theme plays on solo piano, the Loss and Remembrance Theme, slow and thoughtful, expressing in equal measure sorrow and regret, a warm yet sad memory. Randy Kerber’s reading is beautiful, the halting phrases of the theme capturing a quiet sense of loss and the toll of war. A repeating string rhythm starts a slow tug, piano first striking paced rumbling chords underneath, the music expressing deliberation, slow wait for a moment of decision, pensive clarinet and bassoon appearing underneath the rhythm, which transitions briefly from strings to the woodwinds and then back again continuing inevitably and finally slides into resigned silence. 6. “With Malice Toward None” (01:50): String orchestra performs the main theme of the film with sensitivity and grace, the melody in equal part hymnal and traditional folk music, the nobility, humane spirit and a sense of wisdom captured in this gentle lyrical melody. One of the highlights of the album full of emotion and tenderness of Williams’ best themes, the only downside being that it feels too short and I would have loved to hear Williams develop this theme further. 7. Call to Muster and Battle Cry Of Freedom (02:17) Williams includes on the album this resounding reminder of the music of the Civil War era, a piece of diegetic music for militaristic drums and choir, where the traditional sounding military snare drum tattoo with a lively piccolo melody bookends a performance of a famous Civil War era song Battle Cry of Freedom sung by the Chicago Symphony Chorus with patriotic resolve. 8. The Southern Delegation and the Dream (04:43) Somber strings and subdued militaristic brass calls give away to a solo trumpet intoning a tragic and dark melody above string harmonies, paced by subtle timpani, the atmosphere grave. The same grimly martial mood continues and after a brief passage for snare drum, elegiac strings and solo trumpet the music suddenly plunges into disturbing rumbling synthesizer textures and turbulently quivering murkily dissonant string layers, like a musical depiction of a nightmare. High strings slowly rise from the dark cloud of sound and begin a reading of the Elegy Theme, a mournful, lonely and subtly religioso composition, which seems to lament the tragedy of the Civil War and the countless victims of the conflict, the tone of the music forlorn and sad although the piece seems to find some measure of solace in the end. An interesting mix of moods, this piece conjures up shades of the darker and more challenging music and elegiac writing from Born on the Fourth of July, Nixon and JFK. 9. Father and Son (01:42) A solo bassoon presents a halting ruminating melody that moves on to a noble but grave horn statement before melting into a variation on the Freedom’s Call theme on celli and basses, a brief lyrical solo oboe phrase transitioning back to the theme, this time heard in a simple affecting solo piano reading, suggesting a moment of paternal wisdom. 10. The Race to the House (02:41) (Traditional, arranged and performed by Jim Taylor ) A selection of Civil War era folk music titled The Last of Sizemore arranged and performed by the traditional and folk music expert Jim Taylor and licensed from his album The Civil War Collection. A jaunty jig for fiddle, banjo, guitar and hammered dulcimer that contains excerpts from "They Swung John Brown To A Sour Apple Tree", "Three Forks of Hell", Last of Sizemore" and Republican Spirit". Another track that offers some authentic diegetic music from the era and at the same time some lighter tones amidst all the serious and solemn music. A very entertaining piece of music. 11. Equality Under the Law (03:11) A dreamy clarinet solo over expectant string harmonies plays the American Process theme before whole string section takes up the phrase, hinting at the Freedom’s Call’s harmonies before horn and clarinet in somber mood move to a humble statement of American Process theme. Clarinet and flute pair to perform the Freedom’s Call again, this time with solemnity, developing the original melody further until string section rises through this build-up finally to a beautiful yet restrained and reverent reading of this idea that poignantly rises higher and higher, a powerful and emotional musical moment before subsiding in warm harmonies in a classic Williams style. Another winner track, the slow build through the cue reaching a highly satisfying release at the end of the piece. 12. Freedom’s Call (06:06) Tubular bells toll quietly over glowing strings that flow into a solo violin rendition of the With Malice Toward None, a soulful and yearning performance by Robert Chen of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, the melody gently underlined by simple guitar chords. The solo is full of poignancy and idealism yet the violin lends the melody touching emotional fragility that would melt the hardest of hearts. The string section continues to develop the theme, finding new avenues for it and in solemn beauty raises the music to a magnificently emotional height. After the theme has subsided clarinet and bassoon appear together, duetting and performing the American Process Theme that is taken over by the brass in almost heraldic proclamation, the theme working in this piece as a bridge melody that ushers in high strings that play the Freedom’s Call theme in its more developed and emotional guise while rhythmic figures on the double basses play underneath with a feeling of determination, the performance full of stately largesse and sense of accomplishment. Horns and trombones continue the theme reaching a triumphant peak with sense of finality when Williams suddenly releases an ethereal almost beatifically glowing variation of the theme on strings and ends the piece in a noble horn soliloquy by Daniel Gingrich. A stunning composition by the Maestro, drawing together the three central themes of the film. The music is combining moods similar to those of Saving Private Ryan, War Horse and the fiddling of Mark O’Connor from The Patriot. 13. Elegy (02:34) This track is a long development of the Elegy Theme that was previously hinted at on the track The Southern Delegation and the Dream. It opens with a duet for trumpets in almost military bugle call style singing the main melodic line of the sorrowful and tragic theme before the strings come in and repeat the theme in harrowing tones, Williams’ elegiac writing strong and lyrically moving as usual, the performance of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra highly emotional, the mood alternating from sadness to heart rending pathos and finally to religioso majesty, which ends the piece in a resigned calm. 14. Remembering Willie (01:51) After a few harp notes, solo violin and viola receive their own passages, subtly quoting the Elegy Theme before the cello takes over and sings forlorn above simple guitar chords until Loss and Remembrance Theme appears on the solo piano as mourning and contemplative as before, now further enhanced by the sonorous emotionality of the solo cello that appears in brief duet with the piano, expressing quiet but powerful sorrow and feeling of loss. The fragile tone of the music is just superb here, this brief but powerful piece full of emotion. 15. Appomattox, April 9, 1865 (02:36) Horn calls out alone, solemn and slightly mournful and a piano variation on the Freedom’s Call plays serene and unadorned, Williams relying on the simplicity of the most domestic of instruments to carry the emotion and message of the moment, before brass chords slowly flow into heart breakingly beautiful, ethereal sounds of ghostly choral voices, a moment of haunting sorrow, followed by solo clarinet and horn both equally sorrowful and pensive, deep woodwinds and strings bringing the cue to an ending full of dark foreboding. 16. The Peterson House and Finale (11:00) This piece draws together all the themes of the score into a long tone poem styled piece, meditation on all that has gone before on the soundtrack, a stunning and emotional finale. Oboe starts off alone, wandering and ruminating when solemn chords appear halfway between the opening of several of the main themes, showing their interconnectedness, but finally clarinet and flute settle on Freedom’s Call in a humble setting, oboe and cor anglais interrupting, a hint of the Elegy Theme darkening the mood. Reverently slow the With Malice Toward None rises in the strings, Williams omitting a few folk song styled decorative notes here and there in the melody to transform the theme into a more hymn styled variation, a regal deep brass choir repeating the theme full of telling solemnity, slow and dignified in their progressions from which the People’s House Theme begins in the flutes and surges quickly up into a fantastically triumphant full ensemble statement of the theme that slowly fades into a solo trumpet stating the 4-note motto of the idea. The American Process theme on its emblematic woodwinds, clarinet and flute, appears and soon leaps into glowing and courageous string rendition that is followed by a heraldic trumpet solo interlude, showing again the skills of Christopher Martin, his voice sounding like a lonely bugle over a field of battle. From this grows the Freedom’s Call theme in the high strings with the rhythmic low string accompaniment, here perhaps even more expressive than on track 12 and it marches forth, the theme statelier here than ever before. The solo trumpet returns singing With Malice Toward None in serene, warm and clear tones over piano chords, a stunning moment of Americana before the piano continues alone performing an innocent and down to earth variation on the American Process Theme, flute appearing to ghost the theme and in the final reassuring chords the music seems to fade into silence accompanied by a swaying string figure but Williams gives the last word to the Loss and Remembrance Theme, its somber and sorrowful notes bidding farewell to the listener in bittersweet thoughtful tones. 17. “With Malice Toward None” (Piano Solo) (01:31) A solo piano rendition of With Malice Toward None theme rounds out the album in a gentle, pensive mood, Randy Kerber’s performance liltingly warm and even nostalgic, a great finale to the entire listening experience. *** Lincoln is a very strong entry in Williams’ dramatic ouvre and on album it is a highly entertaining and listenable score, permeated strongly by the spirit of Americana. It might not break radically new ground in its approach for such a subject matter but it makes up for it in engaging thematic material, emotional soloist performances and a strong dramatic arc. While the score does make an instant impression with its melodic nature and warmly emotional tone, this is music that benefits from multiple listens, the thematic ideas intertwining through the album so that it takes a few listens to explore Williams composition in full and appreciate the way he approaches the subject matter and Lincoln's different facets. Those who come to this score expecting for the music to impress with bold brassy themes, sweeping statements and grand musical gestures or some kind of complete reinvention of the composer's style might be disappointed but all I can say as a fan of his intimate scores for dramas, his writing for solo instruments and his trademark Americana, this is another wonderful and heartfelt score from the Maestro and shows yet again how Williams is still at the top of his game and going strong at the age of 80, continuing to create some of the best film music around. Lincoln is definitely among the best of the year for me for its mastery of the idiom and sheer emotional appeal. © Mikko Ojala Credits: Music composed and conducted by John Williams Performer: Chicago Symphony Orchestra / Chicago Symphony Chorus Violin: Robert Chen Trumpet: Christopher Martin Clarinet: Stephen Williamson Bassoon: David McGill Horn: Daniel Gingrich Piano: Randy Kerber Additional Musicians: Charles Bisharat fiddle George Doering mandolin Alan Estes, Don Williams percussion Tommy Morgan harp Michael Valerio arco bass Producer: John Williams Editor: Ramiro Belgardt / Robert Wolff Recording Engineer: Shawn Murphy Mixing Engineer: Shawn Murphy Engineer: Brad Cobb Contractor: Sandy De Crescent Preparer: Jo Ann Kane Music Service Mastering Engineer: Patricia Sullivan Update: Film Cue List and approximate correspondence with the soundtrack album I have tried to figure out how does the soundtrack album line up with the film and how much of it is used in the movie and how much left out. Below is a break down of the score in the film cue-by-cue with track times to indicate pieces found on the album. This list contains a rough estimation as some cues sound very similar to the music on the CD but might be different takes. The track titles are either taken from the soundtrack album or the FYC promo and where none is found I have made them up myself. 1. Quickstep and the American Process/ The Dream (1;36) (OST track 7, approx. 0;00-0;32, 1;40-end + unreleased 0;30 + OST track 8, approx. 2;20-3;04) FYC CD track 1: Quickstep and the American Process The film version uses only a short portion of the Call to Muster found on the OSTberfore transitioning to the unreleased piano section and the music for the dream. 2. Sleeping Tad (1;42) (OST track 9) FYC CD track 2: Sleeping Tad 3. With Malice Toward None (0;48) (OST track 4, approx. 2;09-3;01?) FYC CD track 3 With Malice Toward None The OST section is probably an alternate take or a more fleshed out version of this variation of the American Process Theme made for the album. 4. Getting Out the Vote (2;25) (OST track 3, (2;49)) FYC CD track 4: Getting Out the Vote The album version is slightly longer than the film cue, which sounds like editorially shortened and looped. 5. The Southern Delegation Arrives (2;13) (OST track 8, 0;00-2;01) FYC CD track 5: The Southern Delegation Arrives On the OST the music crossfades with the dissonant Dream music. 6. Remembering Willie (1;41) (OST track 13) FYC CD track 6: Remembering Willie 7. Fort Fisher Is Ours (0;39) (Unreleased) 8. Trouble with Votes and Voters (1;20) (OST track 10, approx. 0;29-1;57) Non-Williams material. The music differs slightly from the OST counterpart, the music edited at various points. 9. Message from Grant and Decisions (2;35) (OST track 5, 1;01-end) FYC CD track 7: Message from Grant and Decisions The OST is missing some material and a clean opening. 10. No Sixteen Year Olds Left (1;51) (Unreleased) FYC CD track 8: No Sixteen Year Olds Left 11. The Telegraph Office (1;44) (OST track 1, 0;00-0;48 + track 12, 4;46-5;05 + track 1, 3;07-end) This piece is comprised of the clarinet and flute opening of track 1, which is edited into a short snippet of the Freedom's Call (track 12) and then quickly goes to the track 1 again. FYC CD track 9: The Telegraph Office 12. The Purpose of the Amendment (1;28) (Unreleased) FYC CD track 10: The Purpose of the Amendment 13. Equality Under the Law (1;34) (OST track 11, 1;37-end) FYC CD track 11: Equality Under the Law 14. The Military Hospital – The Argument (Unreleased) (1;35) 15. Persuading George Yeaman (0;27) (OST track 11, 1;09-1;36) 16. Mr. Hutton (0;59) (Unreleased) 17. Welcome To This House (1;41) (OST track 2, 0;00-1;40) FYC CD track 12: Welcome To This House 18. Race to the House (1;12) (OST track 10, partially unreleased) This piece mixes both the authentic folk music snippet from track 10 of the OST with a short new variations on the Getting Out the Vote (track 3) material which is editorially spliced together. 19. The American Process (2;26) (OST track 4, 0;00-2;10, (alternate)) The OST album contains an alternate version of the cue with different ending. FYC CD track 13: The American Process 20. Battle Cry of Freedom (0;50) (OST track 7, approx. 0;33-1;39) This is probably for the large part the same performance heard on the soundtrack album. 21. Thaddeus Stevens Returns Home (1;44) (OST track 2, 1;40-end, alternate) (Film version: unreleased opening section + OST track 2, 1;40-2;24 + 0;55-1;40) The version on the album is probably an alternate. The film version seems to combine a short unreleased opening section with the music found on the OST plus some tracked music from the Welcome to This House cue (incidentally found on the same track on the OST). 22. Lincoln Responds to the Southern VP (1;18) (Unreleased) FYC CD track 14: Lincoln Responds to the Southern VP 23. City Point (1;16) (OST track 5, approx. 0;00-1;00) FYC CD track 15: City Point The album cue crossfades with the Message from Grant and Decisions material. 24. Lincoln and Grant/Lee’s Departure (1;57) (OST track 15 (Alternate) (2;38)) FYC CD track 16: Lincoln and Grant/Lee's Departure 25. Trumpet Hymn (1;06) (Unreleased) FYC CD track 17: Trumpet Hymn 26. Now He Belongs to the Ages (2;47) (OST track 16, 0;00-2;47) FYC CD track 18: Now He Belongs to the Ages 27. End Credits (8;13)(OST track 16, 2;47-end) FYC CD track 19: End Credits Entirely or mostly unused pieces/concert suites: Track 1: The People's House: Aside from the opening, the whole middle section with the People's House theme and the whole American Process Theme are unused in the film. Track 6: With Malice Toward None: A concert arrangement of the theme. Track 8: Southern Delegation and the Dream (3:05-end): A variation on the Elegy Theme, which was entirely discarded in the film. Track 12: Freedom's Call: Again only a small snippet was used in the film, edited together with the music from the People's House track. Track 13 The Elegy: This theme is unused and its placement in the film is uncertain. Track 17: With Malice Toward None (Piano Solo): A concertized solo piano version of the theme. Warning the following contains spoilers! The Complete Score Analysis Lincoln is among the most subdued of the Spielberg/Williams collaborations in terms of the amount of music and its function in the film. John Williams has spoken in several interviews of trying to work underneath Tony Kushner's wonderful script and enhance the words and not to be a too obtrusive partner to the images. The composer was also extremely aware of the style and focus of the film and he and Spielberg use the music more as a subtle support for the drama than as a forefront participant in the storytelling. On the other hand the score works in a very traditional way by accenting the small beats and nuances of the scenes, fleshing out the emotions, the subtext often the unseen emotional turmoil of the main characters. It underscores the important turns of events in the film, facilitates transitions and provides humour but there is audible restraint working in the music throughout, the composer approaching the subject with obvious reverence (for good and for ill), the music rarely rising above a gentle whisper. As scoring approach is restrained and almost reverent, the composer chooses to enhance the positive qualities of the main character with various themes, all drawn seemingly from the Americana vocabulary of the times but still carrying Williams' indelible musical stamp on them. His inspiration were indeed the hymns and folk music of the 19th century but he has chosen rather to channel them through allusion than try to employ a completely authentic approach involving rigorous scholarship or strict recreation of the music of the times. Williams also focuses much of the time on soloists of the Chicago Symphony, their numerous solo parts and duets and trios throughout the score evoking an intimate lyrical atmosphere. Williams by his own word recorded over 90 minutes of music with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and Chorus but only about 40 minutes of this material ended up in the finished film. The soundtrack album contains a good portion of this music but a few sections still remain unreleased. The CD also includes much music that went unused in the film or these pieces were perhaps meant as concept compositions that would enhance the album listening experience as they are obviously well rounded pieces in their own right. A For Your Consideration album was sent at the eve of the Academy Award season to the voters, which presumably contains the music as it is presented in the film (by Academy rules) and also is the source of some of the track titles in the below track-by-track analysis. Themes Freedom’s Call (The 13th Amendment): A short and direct melody, composed of a series of a few alternating chords, depicting Lincoln’s just and good aspirations and goals, the 13 Amendment and the abolition of slavery and his gentle wisdom and noble humanity. There is stately grace in this simple yet affecting idea, bridging the public and personal side of Lincoln and Williams offers numerous alternating variations of it throughout the score in different settings from solo piano to brass chorale. The music connects especially to the moment when a group of blacks for the first time in the history of United States arrive at the People’s House to observe the vote for the Amendment. As stated the motif portrays Lincoln's noble qualities and humanity but also the great work of passing the 13th Amendment and ending slavery and naturally becomes the central musical idea that travels through the entire film, appearing more frequently than any other theme in the score. Appears on the album: 02 The Purpose of the Amendment: 0:55- 1:39 and 2:26-end 09 Father and Son: 0:34-0:52 and 1:08-end 11 Equality Under the Law: 1:37-end 12 Freedom's Call: 3:18-5:29 15 Appomattox, April 9, 1865: 0:24-1:08 16 The Peterson House and Finale: 0:24-1:20 and 6:19-7:39 With Malice Toward None: The name of the theme refers to the second inaugural speech of Lincoln and it is a folk song styled, simple, lyrical and honest melody. It seems to embody the down-to-earth nobility of the main character and his humanity. Coloured with lilting gait of folk music in some settings and slow solemn progression of traditional hymns in others, this theme paints a very humble, thoughtful and gentle picture of the president of United States. In interviews Williams said that he started the scoring process from the final scene of the film and worked backwards from there after he had gotten the theme for the inaugural address right. His goal was to find a melody close to the hymnal writing of the times and he mentioned that he had searched for something suitable from old hymnals but in the end found it better to try to convey the spirit of the music of the era and hymns with his own theme for the president. While this theme is frequently used on the album, in the film it appears a scarce few times, the composer reserving it for a few key scenes toward the end of the film, the most pivotal being the finale, where it gains a near beatific character. Appears on the album: 04 The American Process: 1:18-1:47 and 3:10-end 06 With Malice Toward None 12 Freedom's Call: 0:24-2:29 16 The Peterson House and Finale: 1:49-3:13 and 7:40-8:25 17 With Malice Toward None (Piano Solo) The American Process: A gentle lilting Americana "home and hearth" melody with almost folk song quality, the theme pensive yet optimistic with a sense of earthy wisdom. It is set often in the woodwinds, clarinet, bassoon and flute but this idea is also frequently developed on stately strings or brass, revealing a nobler aspect and aspirations in this guise. Williams keys this musical idea to the processes of state, the peace making overtures and especially the actual vote and work at the House of Representatives, the music exemplifying the positive force of democratic process. Appears on the album: 01 The People's House: 2:16-3:09 04 The American Process: 0:00-1:19 and 2:10-3:00 11 Equality Under the Law: 0:00-1:36 12 Freedom's Call: 2:29-3:18 16 The Peterson House and Finale: 4:50-5:43 and 8:26-9:14 The People’s House: The most dramatic and triumphant of the themes, this noble and heroic idea is built on a leaping four note clarinet figure heard initially on the opening track and soon blooms to a full brass and strings setting, imparting a sense of victory and achievement, probably reflecting political and personal accomplishment. The idea is used sparsely on the soundtrack album appearing only on the opening track and the Finale tracks. In the film this motif appears only as a single subtle quote of the opening phrases in one cue, the actual full melody appearing only in the end credits. Appears on the album: 01 The People's House: 0:00-2:15 and 3:10-end 16 The Peterson House and Finale: 3:14-4:49 The Elegy: A mournful and anguished string elegy, quite religioso in nature, that seems to exude regret, sorrow and horror all in one harrowing theme, a reminder of the Civil War and its ravages. This musical idea went entirely unused in the film, the movie makers most likely deciding that the images of war spoke even more powerfully without musical accompaniment. Appears on the album: 08 The Southern Delegation and the Dream: 3:06-end 13 Elegy The Civil War: This theme or motif is more of a set of orchestral colorings, military styled brass calls, snare drums and tense strings conjuring terse martial mood. A few alternating chordal progressions seem to convey the looming threat of the civil war and the military aspect of the political machinations. This style of music is reprised a few times in the film always either directly relating to the Southern Delegation and their military surroudings or the presence and danger of the war, which sets a dark backdrop to the whole story. This is another subtle nod the the direction of Aaron Copland, his work The Lincoln Portrait in particular. Appears on the album: 08 The Southern Delegation and the Dream: 0;28-1;39 The Loss and Remembrance Theme: A theme that seems to relate both to Lincoln's personal loss, of his son William, but also to mourning of the tragedy of Civil War and remembrance of the dead. It is an unadorned piano melody that expresses bittersweet sorrow with a hint of regret. This musical idea is used sparsely and always retains the same guise, invoked on the piano, the most familial and "domestic" but also emotionally direct of instruments. Appears on the album: 05 The Blue and Grey: 0:00-1:01 14 Remembering Willie: 0:29-end 16 The Peterson House and Finale: 9:29-end *** Complete Score Track-by-track Analysis The track names are taken from the For Your Consideration album and Original Soundtrack and where unavailable made up by myself. 1. Quickstep and the American Process/The Dream (1;36) (OST track 7, approx. 0;00-0;32, 1;40-end + unreleased 0;30+OST track 8, approx. 2;20-3;04, FYC CD track 1) Following the unscored bloody opening scene where the black Union men are locked in a hand-to-hand combat with the Confederate forces, president Lincoln is shown sitting under a tent tarp in a military camp where he is having a discussion with two black soldiers. Then two young awed Union soldiers approach as they spot the president and start to recite the Gettysburg Address to the chagrinned commander-in-chief. And none too soon the snare drums suddenly stir and interrupt the men and call the troops to muster (to the tune of the Quickstep march rhythm) before they can finish their rather automaton-like litany. A black corporal Ira Clarke, who has also been conversing with the president, continues to recite the ending of the Address almost as a reminder to Lincoln to heal the war torn nation and set the things right as he promised and a gentle piano rendition of The American Process Theme mixes with the snare drum tattoo, hinting at Lincoln’s important duty and work that still lays ahead of him. The film transitions to the president recounting his dream to his wife Mary, where he was riding a tall metal ship towards an unknown shore and this dissonant rumble in the lowest reaches of the orchestra, a bed of tremoloing strings and sizzling rubbed gong depicting the flickering dream imagery, sepia and grey in Lincoln’s memory, before fading slowly away as he finishes his tale. 2. Sleeping Tad (1;43) (OST track 9, Father and Son) Lincoln comes upon his son asleep before the fireplace with glass plates of African-American slaves sprawled beside his tin soldiers on the floor. A solo bassoon presents a halting ruminating melody that moves on to a noble horn statement as the president looks at the glass plate photos in grave sadness before the score melts into the first variation on the Freedom’s Call Theme on celli and basses, the theme associated here to Lincoln personally but also reinforcing his thoughts concerning the civil war and especially the 13th Amendment, a brief lyrical solo oboe phrase transitioning back to the theme as Lincoln lowers himself beside his son and gently awakens him. This time the melody is heard in a simple affecting solo piano reading, colouring this moment of paternal love as Lincoln carries his son to bed on his back, the familial moment of tenderness gracefully captured by the music. 3. With Malice Toward None (0;48) (OST track 4 approx. 2;09-3;01) After Lincoln makes a journey to the house of Preston Blair, the founder and head of the Republican party, and agrees to have him travel to Richmond to negotiate peace, we see the old man getting ready to leave in his carriage and a hopeful piano variation of the American Process Theme sees him off on his mission, the peaceful solution to the hostilities through negotiations his primary concern. 4. Getting Out the Vote (2;32) (OST track 3, (2;49)) A trio of agents (“skulking men” as the film puts it) is hired and sent by the Secretary of State William Seward to procure the critical votes on Lincoln’s behalf for the amendment. Solo violin nimbly opens this wonderful jaunty Appalachian scherzando or dance for fiddle, viola, woodwinds, tuba, light percussion and strings, the music exuding wonderful folk music feel, energy and humour when we see the various ways these voters are cajoled into changing their stance. The efforts of these three gentlemen are met by various stages of success and the music comments their haggling accordingly as we see them reporting to Seward on their results. The soloists have their moment to shine, violin and bassoon performing particularly delightful solos, the former actually underscoring an on-screen fiddler in the film. This music provides a much needed sense of humour and lightness to the otherwise serious film and Williams has fun with the rather salt of the earth and no nonsense characters of Robert Latham, W.N. Bilbo and Richard Schell. The film version is slightly different than the counterpart on the soundtrack album. Not only it is shorter but also contains repeated phrases to conform to the dramatic outline and beats of the scene. 5. The Southern Delegation Arrives (2;13) (OST track 8, 0;00-2;01) William Seward confronts Lincoln concerning the rumours of a Southern peace delegation arriving to Washington through the efforts of Preston Blair and somber strings slowly murmur to colour his feeling of apprehension at the notion, especially since the president neglected to consult him, his Secretary of State. When we transition to no-man’s land outside Petersburg, Virginia, subdued militaristic brass calls give away to a solo trumpet intoning a tragic and dark melody, The Civil War Theme, above string harmonies when the opposing forces have arrived to receive and escort the delegation, paced by subtle timpani, the atmosphere grave when the Confederates and the Union men stare at each other in obvious tension. The same grimly martial mood continues and after a brief passage for snare drum, elegiac strings and solo horn, the music suddenly plunges into disturbing rumbling strings when the dismayed delegates find out that majority of their escort is made up of black soldiers but in a show of temperate diplomacy ascend their carriage courteously, the score portending that these will not be easy negotiations. 6. Remembering Willie (1;50) (OST track 13) On the evening of the Grand Reception at the White House Lincoln is alerted of Mary’s sudden harrowing mood brought about by the party and grim memories connected with it. The president hurries to comfort her in Willie’s old room, their son having died 3 years prior during a party in the White House. The depressed and guilt ridden Mary is holding the portrait of their son, a few delicate harp notes and solo violin and viola subtly quoting the Elegy Theme, expressing her sorrow and remorse, the party another reminder of how they lost their child and how they couldn’t save him. As she laments the death and their time in the house that reminds her of it all, solo cello takes over and sings forlorn above simple guitar chords until Loss and Remembrance Theme appears on the solo piano, inconsolable and contemplative, further enhanced by the sonorous emotionality of the solo cello that appears in brief duet with it. The instruments express quiet but powerful feeling of grief and the parents' loss, the fragile tone of the music capturing both the tender bond between the pair and their shared sad memory as Lincoln gently urges his wife to stay strong. 7.Fort Fisher Is Ours (0;39) (Unreleased) Lincoln and his Secretary of War Edwin Stanton are in the midst of the nervous bustle of the War Department telegraph office monitoring the progress of the assault on Wilmington. Stanton is on edge and when the president goes into one of his stories the secretary storms out to oversee the war effort in less of a storytelling atmosphere. When he returns one of the telegraphs operators announces the news: Fort Fisher has fallen but Wilmington itself has not surrendered. Tense heavy and slow bass drum strokes amid grave low string chords announces the sour victory for the North as both the president and the secretary look alarmed and dismayed demanding to know the tally of casualties, the music portending heavy losses and further bad blood between the contending parties. 8. Trouble with Votes and Voters (1;20) (OST track 10 approx. 0;29-1;57) A selection of Civil War era folk music arranged and performed by the traditional and folk music expert Jim Taylor. A jig for fiddle, banjo, guitar and hammered dulcimer that contains excerpts from "They Swung John Brown To A Sour Apple Tree", "Three Forks of Hell", Last of Sizemore" and “Republican Spirit" underscores more efforts to get votes from rather reluctant Democrats, the troubles and unlucky incidents accented by this folksy and spirited music. Here the film makers saw an opporturnity to colour the characters of W.N. Bilbo and comrades and their rather unscrupulous dealings with sprightly humor and inject the score of the film with earthy and suitably playful music of the times. 9. Message from Grant and Decisions (2;35) (OST track 5, 1;01-end) Meanwhile General Grant has had discussions with the Southern delegates and telegraphs the president that someone of authority in the government has to come and negotiate with them or the opporturnity for peace will be lost. Seward in his usual habit presents Lincoln with the options, setting the peace and passing of the 13th amendment side by side, leaving the president to make the final decision, adding that he cannot hope to have both. A repeating string rhythm starts a slow tug, piano first striking paced rumbling chords underneath, the music expressing deliberation, slow wait for a moment of decision, pensive clarinet and bassoon appearing underneath the rhythm which transitions briefly from strings to the woodwinds and then back again continuing inevitably and finally slides into resigned silence when we see Lincoln torn over the chance of peace and the chance to end the slavery, both seeming to exclude each other at this juncture, the music enhancing the mood of his troubled pondering and the underlinining the high stakes of his decision. 10. No Sixteen Year Olds Left (1;51) (Unreleased) Lincoln, who is plagued by heavy burdens of the state and his important decision, can’t sleep and thus works through the night. He appears at the bedside of his young aides in the small ours of the morning, waking them up and arguing to the bleary eyed young men of the Stanton's decision of executing 16 year old private for laming his horse to avoid going to battle. He wants to pardon the boy, but the aides say that Secretary of Defence Stanton is against pardons to deserters. A pensive clarinet solo underscores Lincoln’s weary sorrow for such wasteful death and as he mentions to the surprise of his young assistants the Southern peace delegation and the rumours being true after all, the celli sing out a somber line. But when the president switches back to the issue of the young soldier, finally deciding to pardon him, an optimistic string phrase and noble solo horn quote the stately but stoic military brass colours of the Civil War Theme but here the mood is optimistic and resolved, the music blooming into a tentative reading of the first chords of Freedom’s Call Theme as Lincoln heads for the War Department telegraph office, the transition earning another statement of the military material pertaining to the peace delegation, now on glowing woodwinds. 11. The Telegraph Office (1;44) (OST track 1, 0;00-0;48 + track 12, 4;46-5;05 + track 1, 3;07-end) At the telegraph office Lincoln, while he is sending a reply to general Grant, gets into a conversation with the two young men on duty, the subject Euclid and equality. The president takes the mathematical theorem and expounds on its universal law so that it should apply to people as well as mathematics, the noble sentiments heard in the burgeoning clarinet reading of the opening phrases of the People’s House Theme that is gracefully taken up by the flutes when the president makes up his mind and decides to stall the arrival of the peace delegation, his desire to see the amendment passed winning in his mind and we hear a tenderly glowing strings rise into a short statement of the Freedom’s Call Theme, a trumpet soliloquy of People’s House Theme escorting the president out of the telegraph office, his plans and mind made up. In this piece the composer seems to pay homage to the great Aaron Copland, whose music has become almost synonymous with orchestral Americana, the initial 4-note opening phrase of the People's House Theme quoting the central motif from Copland's perhaps most famous work, the ballet Appalachian Spring. 12. The Purpose of the Amendment (1;28) (Unreleased) Things are coming to a boiling point in the debates at the House of Representatives and Thaddeus Stevens makes his entry in the discussion on the 13th Amendment bill. His word as the leader of the radical Republican wing holds a lot of weight and his colleagues plead him to compromise on his views in his speech and announce that the bill stands only for equality before the law and not universal equality for the blacks. A solo horn opens the cue when Thaddeus Stevens glances at the balcony where Mrs. Lincoln sits watching the debate, the music giving the moment pensive air, Mr. Stevens torn between his own radical opinion and what would be a politically more temperate approach. The solo continues as a Democrat representative Fernando Wood deliberately goads Stevens by proclaiming that he had always previously demanded full equality for the blacks and demands to know if this is still so. When Stevens seemingly struggles with the answer, the Freedom’s Call Theme plays in humble yet proud woodwind setting with subtle lower string accompaniment that rises to the fore, the rhythm of the motif repeating as everybody is holding their breath before Mr. Stevens answers. Solo horn calls out in stately manner as we see the brief moment of inner struggle of the representative, the music stopping just before he announces his stance: Stevens proclaims that the purpose of the amendment is to guarantee not full equality but equality before the law for the blacks. 13. Equality Under the Law (1;34) (OST track 11, 1;37-end) George Pendelton, one of the leaders of the Democrats and rabidly against the amendment, accuses Stevens of turning his coat and prevaricating. Stevens then repeats his stance, Freedom’s Call Theme starting a slow development on clarinet, flute and bassoon, Williams extending the theme’s melody ever so slightly as the leader of the Republican’s ends his scatching speech on equality before the law on a triumphant note, the Republican party members cheering, the orchestral strings blossoming into a soaring and unabashedly hopeful reading of the Freedom’s Call Theme, which continues relieved and confident as he walks slowly out of the House chamber after finishing his speech, the score celebrating this smaller stepping stone and victory on the road to abolishing the slavery. 14. The Military Hospital – The Argument (Unreleased) (1;35) Lincoln is visiting the military hospital accompanied by his eldest son Robert, who sulkingly accuses his father of deliberately trying to dissuade him from enlisting by bringing him along to see the wounded and the dying. Defiantly he says that he knows all about the horrors of war and that his father won’t turn his head. To all this Lincoln answers with apparent good natured calm. As the president goes about his official business of meeting the wounded, Robert sees two soldiers carting off a covered bloody heap on a wheelbarrow, their work leaving a grim red trail behind them as they go. He follows and sees to his disgust and horror that they were transporting amputated limbs to be buried, all unceremoniously dumbed into a pit behind the hospital. Robert walks away shaken and a tragic call of a solitary horn over whispering high strings exclaims his shock and sorrow. He stiffles a sob and when his father appears elegiac strings sing out the younger man’s defiant wish to enlist, the suffering of war only steeling his resolve and adding to his frustration. Lincoln understands but reminds him of the suffering of those, who have to give up their children to war, Freedom’s Call Theme humanely calling out his fatherly concern on warm brass as the president dispenses this wisdom as a father not as a head of state but he also reminds his son that he is the president and can decide on his enlistment if he so wishes. Robert snaps that his father is just afraid of his mother and what she might do or say, which suddenly provokes a slap from the president, the music turning tragic and ominous as Robert storms off shouting, the solo trumpet and accompanying grim horns quoting the militaristic mood of the Civil War Theme once more, the threat of war and death looming in the music as Lincoln wearily exclaims in half-whisper that he doesn’t want to lose his son to the civil strife. 15. Persuading George Yeaman (0;27) (OST track 11, 1;09-1;36) One of the uncertain Democrats, George Yeaman, is invited to the White House to a discussion with the president. Lincoln in his typical way starts a story, this time about him and his father, but finally makes an honest plea to the representative to vote for the amendment, arguing his case emphatically. Solo clarinet in equally pensive style opens this short cue and as he makes his final plea the American Process Theme on woodwinds and brass seems to ask a decision from Mr. Yeaman before trailing off into silence. 16. Mr. Hutton (0;59) (Unreleased) A somewhat gloomy clarinet and bassoon duet underscores Lincoln’s attempt to persuade Mr. Hutton, another Democrat representative, to vote for the amendment. The man refuses as he holds a deep grudge against the blacks as his brother died in the Civil War and the music remains stoic and melancholy as the clarinet and bassoon continue their discussion. Lincoln then says he is not going to try to turn Mr. Hutton around with any more speeches and that the amendment will likely pass without his help and that he has to acknowledge that the black people will live among the white and the score subtly quotes a few opening notes of the Freedom’s Call Theme before warm string phrase ends the piece as Lincoln offers his condolences to Mr. Hutton’s family and steps into his carriage having made his case. 17. Welcome To This House (1;41) (OST track 2, 0;00-1;40) And so comes finally the morning of the vote for the 13th Amendment. The stoic melody heard in the previous cue is reprised again on clarinet and bassoon, developing slowly phrase by phrase as Thaddeus Stevens is seen arriving to the empty House floor obviously full of trepidation on the eve of this momentous occasion. The melody moves gradually to flute and clarinet coupling as we see people assembling to the House of Representatives. When Asa Vintner Litton, a Republican representative and a fervent abolitionist, welcomes a group of African-Americans to the House balcony to observe the vote, first such group to ever visit the House of Representatives, a hopeful and warm string reading of Freedom’s Call Theme kindles in the orchestra that steadfastly rises forth on violins and violas, the celli and basses playing accompanying figures underneath. These are finally joined by low burnished brass to celebrate this historical moment, the music itself here winding into silence to observe the vote. 18. Race to the House (1;12) (OST track 10, partially unreleased) The debate preceding the vote for the amendment comes to a standstill when the Democrats demand confirmation to the rumours of Confederate peace delegation in the capital and thus of postponing the vote until a peace has been negotiated. The conservative Republican wing joins with the Democrats in their request under orders of Preston Blair and soon the president’s aides and N.W. Bilbo are rushing to the White House to inform Lincoln and asking him for the answer to the Democrats’ question. Williams answers this scene with a brief humorous scherzando, which editorially combines his motif for the “skulking men” heard in Getting Out the Vote and the traditional folk music melodies, when we see the trio of men running from the Hill to the White House in breathless hurry to deliver their message and to save the vote for the amendment. 19. The American Process (2;24) (OST track 4, 0;00-2;10, (alternate)) The vote is finally drawing to a close and Williams underscores the action with the American Process Theme that evokes in its honest simplicity the rightness of the democratic process. A duet of clarinet and bassoon sings the theme alone for a moment when representative Alexander Coffroth announces his “yes” vote and soon a solo flute joins in, the action moving to the headquarters of General Grant where the troops are intently following the tally through the telegraph. The orchestrations gather strength as the woodwind section finally reprises the melody in full form as votes are cast one by one by the representatives. In the White House Lincoln is seen sitting with his son Tad in his lap reading a book together and a serene and familial oboe solo expresses a tender and calm personal moment for the president in juxtaposition to the historical event taking place at the House of Represetatives, the deep and warm strings carrying the score back to the House where the roll call is concluding. A sustained chord in high string plays as the Speaker of the House Colfax announces suddenly that he wants to cast a vote and George Pendelton objects the rarely used priviledge as subdued clarinets play a dour phrase. Stately brass announces the Speaker’s “aye” vote and concludes the tally, strings rising with noble intent as the clerk hands the document to Schuyler Colfax, the cue ending in another sustained chord for suspense as he slowly reads the results. 20. Battle Cry of Freedom (0;50) (OST track 7, approx. 0;33-1;39) The 13th Amendment passes and the Republicans rejoice, the representatives beginning an impromptu chorus of Battle Cry of Freedom, a popular patriotic Civil War era song by George Frederick Root and the unofficial tune of Lincoln’s second term campaign. The song gradually morphs from the rough version sung out of tune at the House floor into a full chorus and orchestra, here performed by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and Chorus, first male voices and then female joining with them when Thaddeus Stevens is seen taking the bill of the Amendment and walking home through the streets where people are celebrating, the song proudly calling out as a victorious march on this historical occasion. 21. Thaddeus Returns Home (1;44) (OST track 2, 1;40-end (Alternate)) (OST track 1;40-2;24 + 0;55-1;40) The orchestra starts tentatively when Thaddeus Stevens closes his door and is welcomed by his black housekeeper and he hands her the Amendment as a “gift”, the melody in the strings and woodwinds reminiscent of the one that opened the Welcome to This House cue. Clarinet passes a proud and confident melodic phrase to horns and finally to solo trumpet as Stevens is seen getting into bed, where his housekeeper is already seen sitting with the bill in her hands and a gentle and tender clarinet voices the man’s affection for her. She begins to read the Amendment aloud to him and Freedom’s Call Theme is evoked by Williams in its proudest and most resolute form yet, a musical reassurance of the values inherent in the document and the crowning moment to Mr. Stevens in his struggles against slavery, which as we now see has also had a very personal motive. 22. Lincoln Responds to the Southern VP (1;18) (Unreleased) After the passing of the 13th Amendment the president travels to meet the Southern delegation and their leader the Confederate Vice President Alexander Stephens. Both parties express their views at the negotiation table, the Confederates bitter and resentful of their lot and the recent passing of the amendment. As Lincoln expounds upon the ideal of democracy and its longevity, the futility of further bloodshed and war, a ruminating bassoon solo above subtle string accompaniment supports his words with quiet lyricism. Strings slowly grow more insistent as the tension grows and the same turbulent orchestral rumbles that underscored Lincoln’s nightmare at the opening of the film are suddenly quoted when the president makes a plea to stop the war, the question left ominously hanging in the air unanswered, the image dissolved into a raging inferno of a town burning in the night, a grim nightmarish visage of the destruction of the Civil War. 23. City Point (1;16) (approx. OST track 5, 0;00-1;00) Outside Petersburg, Virginia Lincoln arrives at the scene of a recent battle, the land torn and burning, the countless dead, the Blue and Grey, lying side by side in the middle of the carnage. As the president rides amid the battle field a touching and unadorned rendition of the Loss and Remembrance Theme plays on piano, the head of state taking off his stove pipe hat and honoring the fallen soldiers as he passes in silence through the fields of the dead, the music giving the moment a poignant but mournful cast, the weariness brought on by this long suffering reflected in the president’s face and in the score. 24. Lincoln and Grant/Lee’s Departure (1;57) (OST track 15 (alternate) (2;38)) The piece opens with an unused section of music. Lincoln meets with general Grant at the Thomas Wallace House at Petersburg, where he holds his temporary headquarters. A horn calls out alone, solemn and remorseful as the two men share a moment while sitting on a porch by the roadside, the horror of the field of the dead still fresh in the president’s mind. A piano variation on the Freedom’s Call Theme serene and unadorned with a tinge of regret appears, Williams relying on the simplicity of the most domestic of instruments to carry the emotion and message of the moment, when Lincoln admits to Grant they have allowed each other to do terrible things, the gentle tone of the music almost rueful here as Lincoln is still shocked by the death he has seen, a concrete reminder of the toll of war. The general admits this but also says that they have won the war and that now Lincoln should focus on healing the nation. Slow and solemn brass chords (unused in the film) flow into heart breakingly beautiful, ethereal sounds of ghostly choral voices of the Chicago Symphony Chorus that seem to evoke the voices of dead of the Civil War as much as they mark this important moment of history as we see general Lee surrendering to general Grant and effectively ending the war. Here the significance of the relatively small and intimate scene and all the historical ramifications are carried by the score, which magnifies the near everyday scene with dramatic subtextual meaning. Solo clarinet carries a defeated and somber tones as Grant magnanimously salutes the defeated general with his men, horn answering for general Lee, both equally sorrowful and pensive, deep woodwinds and strings bringing the cue to a gloomy finale as the Confederate commander rides away from the Appomattox courthouse in silence, the music mirroring more the mindset of soldiers and their honor, won and lost, than the relief at the end of the civil strife. On the album this piece is slightly longer than in the film, opening with a solo horn soliloquy, which then proceeds to the Freedom's Call Theme. In the film the score opens with the Freedom's Call Theme on piano but in different key and omits the longer bridge between it and the choral section. 25. Trumpet Hymn (1;06) (Unreleased) And so the rebuilding of the nation can begin. At the White House Lincoln is holding a meeting with the Speaker of the House and select representatives, when his aide comes to remind him of his engagement at the theater and that he should be leaving to pick up his guests. Lincoln’s black valet Mr. Slade hands him his gloves and the president proceeds to leave and all the assembled rise to see him off and a solo trumpet sings With Malice Toward None in poignant spirit, the music speaking clearer than words for the significance of the moment, the noble yet earthy decency captured in the melody, the music equivalent of a goodbye as the president exclaims almost wistfully "I suppose it’s time to go, though I would rather stay". The president throws away the leather gloves that he distinctly dislikes and his servant tries to catch up with him but stops at the last minute and turns to take a look at Lincoln with some premonition in his eyes. Williams catches this foreboding by weaving a subtle strain of the supporting chords of Loss and Remembrance Theme into the score on piano as we see the figure of the president slowly walking down the hall and disappearing from view, the trumpet’s voice receding into silence with him, the scene and music full of poignant inevitability. Williams originally composed this cue for Lincoln's ride through the battlefield at City Point but the piece was unused in that scene. Instead Spielberg moved it in this scene where it provides a poignant final salute to the president before the assassination. 26. Now He Belongs to the Ages (2;47) (OST track 17, 0;00-2;47) The president has been shot (this happens off-screen) and we next see him when he has been taken to the Peterson House near the Ford Theater, where he has lain through the night. Oboe begins the piece alone, wandering and ruminating full of aching grief as near hysterically weeping Mrs. Lincoln is escorted out of the room, where she has just seen her dying husband. The cabinet ministers, the doctors, president’s aides and his eldest son Robert have gathered around the deathbed and slowly solemn chords appear halfway between the opening of several of the main themes, showing their musical interconnectedness and common source in Lincoln's character when a physician finally announces the president dead. When Edwin Stanton the Secretary of War exclaims “Now he belongs to the ages” clarinet and flute settle on Freedom’s Call in a humble setting as the camera glides away and moves to the flame of a lamp and we hear Lincoln’s voice reciting his second inaugural address, the president seen at the center of the flame. The speech continues and oboe and cor anglais interrupt the Freedom’s Call melody, a briefest hint of the Elegy Theme appearing as Lincoln reminds the listeners of the horrible cycles of hate and of the punishment for sins of which the slavery is among the worst to his mind and he saw the Civil War as a divine punishment for this. Reverently slow the With Malice Toward None rises in the strings when the president expounds upon the charity and humanity people should show in rebuilding the state, to friend and foe alike as they are still of the same nation. Williams omits a few folk song styled decorative notes here and there in the melody to transform the theme into a hymn styled variation, the string setting reverent and solemn with deep benevolent warmth, the gentle strains of the melody drawing the film to a calm resolution as the screen slowly fades to black. 27. End Credits (OST track 17, 2;47-end) This cue draws together all the themes of the score into a long tone poem styled piece, meditation on all that has gone before on the soundtrack, a stunning and emotional finale. A regal deep brass choir with woodwind accompaniment repeats With Malice Toward None full of calm solemnity, slow and dignified in their progressions from which the People’s House Theme begins in the flutes and surges quickly up into a triumphant full ensemble statement of the melody that slowly fades into a solo trumpet stating the opening 4-note motto of the theme. The American Process Theme on its emblematic woodwinds, clarinet and flute, appears and soon leaps into glowing and courageous string rendition that is followed by a heraldic trumpet solo interlude, showing again the skills of Christopher Martin, his voice sounding like a lonely bugle over a field of battle. From this grows the Freedom’s Call Theme in the high strings with the rhythmic low string accompaniment marches forth, the theme perhaps statelier in its progression here than ever before. The solo trumpet returns singing With Malice Toward None in serene, warm and clear tones over piano chords, a stunning moment of Americana before the piano continues alone performing an innocent and down to earth variation on the American Process Theme, flute appearing to ghost the theme and in the final reassuring chords the music seems to fade into silence accompanied by a swaying string figure but Williams gives the last word to the Loss and Remembrance Theme, its somber and sorrowful notes bidding farewell to the listener in bittersweet thoughtful tones. -Mikko Ojala-

- 66 replies

-

- Review

- John Williams

-

(and 2 more)

Tagged with:

-

-

I have long been thinking about this. Where does being a "fan" end and where does "being obsessed" start? At what point does one stop being a normal, healthy fan who enjoys listening to the music of his favorite composer and when does one become obsessed, that is unhealthy, when the obsession takes over one's life and it becomes a toxic fixation over another person whose work one admires? I'm really curious to hear everyone's opinion on this, in my humble opinion, very serious and important subject matter, because there are certain people who are borderline obsessed with certain composers and they may not be aware of it. When does being a "fan" become being "obsessed" with someone? How much "love" for someone's work and his persona is still healthy and normal, and when does it become unhealthy, toxic and dangerous? Is there a firm line between a "fan" and an "obsessed person" and if so, where does it lie? What are the boundaries no one should ever cross?

-

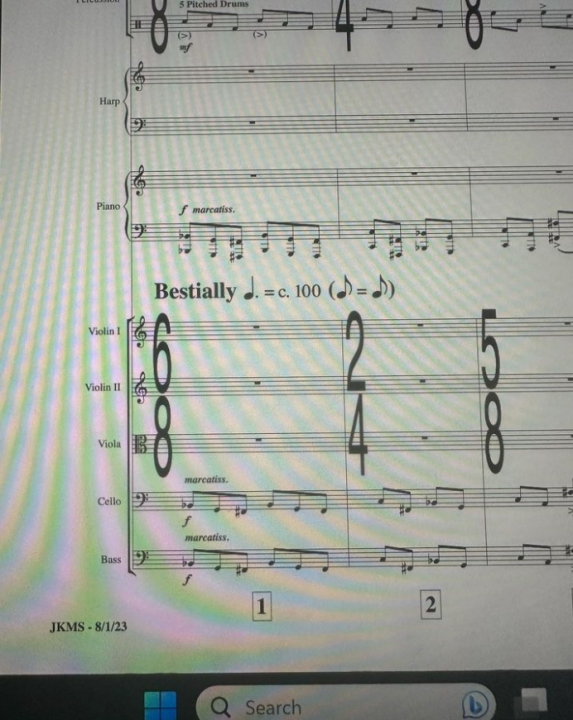

I am creating a second HOOK ULTIMATE EDITION thread, so that people can discuss the music without the conversation being mixed in with shipping updates and general anticipation posts. Here is the original thread where shipping updates, etc should still be shared in Now on to the music! I'm looking forward to hearing more thoughts from you three, as well as anybody else that has received their copy already!

- 454 replies

-

- Hook

- Steven Spielberg

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

The trilogy that forever shattered a fanbase in two. The trilogy that, arguably, scarred the reputation of one of Hollywood's greatest storytellers. The trilogy that, whatever its shortcomings may be, features some of the most badass music John Williams has ever composed. Which film and score do you prefer from the divisive Star Wars prequel trilogy?

-